Leasehold Forestry in Nepal and Inclusion of Dalit : A critical review

Shekhar KC

kushekharkc@gmail.com

Abstract

The central argument of this paper is that leasehold forestry program in Nepal can be taken as an effective forestry strategy to include socially and economically marginalized section of the society including dalit community and address the limitation of community forestry program which has failed to enhance livelihood options of poor people. Starting with the conceptual note on leasehold forestry, this article puts light on various loopholes of community forestry management policies and practices through scholar’s analysis and case studies and explains how leasehold forestry has been acknowledged by scholars as the effective strategy to combat twin purpose of forestry regeneration and poverty alleviation of of poorer groups including dalit community.

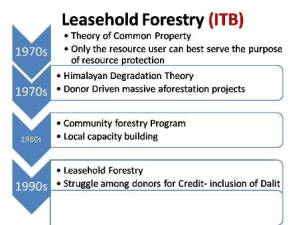

Remaining within the discourse of natural resource management, this essay gives insight to different Inside the box(ITB) theories including Himalayan Degradation Theory of 1970s and theory of common property regime and their linkages to emergence of leasehold forestry in Nepal. Alongside, the scholarly attempt has been made to link leasehold forestry with the diverse ‘outside the box’ (OTB) developmental thinking in Nepal including top-down and bottom-up approach to development, changing role of state from developmentalist state to neoliberal agenda of development where role of state is minimized and the market is emphasized. through those OTB and ITB linkages to development and environment discourses, this essay attempts to locate and emphasize the contribution and need of leasehold forestry in the natural resource management sector of Nepal by addressing the poorer community including Dalit.

Finally, this essay concludes that dalit inclusion in forestry management serve the twin purpose of sustainable natural resource management and simultaneously opens the livelihood options for poorer and marginalized communities by securing their legal access to the land and forestry resources.

Introduction to Leasehold Forestry in Nepal

Leasehold forestry is a community forestry management program which involves the set of policies, programs and laws that guides the management of forest by targeting poorer and socially excluded section of the society. The program intends to enhance the livelihood strength of the backward and underprivileged people though social inclusion and pro-poor projects and programs. Leasehold forestry legalizes the access of socially marginalized and poor people to the degraded land[1] and forestry resources and hence guarantees the exclusive property right to target poorest household.

Figure 1: Conceptual development from Community forestry to leasehold Forestry in Nepal

Failure of Community Forestry Programme

The initiation of Community Forestry Programme can be traced back to 1978 and has been acknowledged as a successful strategy in giving communities access to forest resources and improving forest management. However its over concerns for revenue collection through selling timber product has resulted in the ignorance to the protection and utilization of non-timber forest resources, especially forage and has not considered much about enhancing the access of poor and disadvantaged groups to such resources (Pande, 2009).

Community forestry programs though has got considerable positive comments however has been criticized on various grounds. Particularly its unfair criteria to facilitate access of rich and elite, landlords to the forestry product in one way and simultaneously block Poor, especially the landless dalit[2] to be included in the Community Forestry Unser Group member are such grounds.

And hence to cover the loopholes of CFP, Leasehold Forestry program was proposed in 1993 under forestry Act 1993 and subsequent regulation of 1993 with the objectives of stopping forest degrading and address the poorer section of the society, particularly those who don’t have private property around the forest. (Sharma, The Welfare Impacts of Leasehold Forestry in Nepal, 2011). LHF is a kind of contractual private property right on land intended for environmental regeneration with the final ownership to the state.

The LHF possesses twin characteristic: firstly, it is a land redistribution (land reform) programme that provides the poor with property right on land to work with and; two, it is a special environmental programme aimed at regenerating degraded and ecologically fragile lands (Sharma, A Proposal Submitted to SANDEE for Fall 2006 Research Competition, 2006).

The basic idea is to enhance non-timber forest regeneration while also making it possible for LHF land to meet basic livelihood needs of socially marginalized and landless groups of society. The program expects LHF households to enhance their income in a sustainable manner from both livestock, due to improved fodder availability, and timber and non-timber forest products (Sharma, 2011).

Dalit inclusion through leasehold forestry

About 20 percent of the total land in Nepal is suitable for cultivation with agriculture and forestry is the major economic activity engaging about 65 percent of the total population (Sharma, 2011).

Jayaswal and Oli (2003) claims that the poor and the disadvantaged are marginalized from the use rights they had been practicing since generations. Saxena (2002) has pointed out that the pro-poor property right regime in the management of the degraded land was missing in the community forest management policy and thus LHF programme was undertaken to fulfill the missing component (as cited in Sharma, 2011).

Similarly, Malla (2001) has explicitly underscored the crucial role of active participation of poor, women and disadvantaged groups in building their decision-making capacity. This is expected to bring effective management of the community forest and result in equitable benefit distribution among the users. Since Poorer households, especially those without land, cannot use fodder, leaf litter, and other agricultural inputs from Community Forest, LHF is expected to address the problem and end the decade-long monopoly of better-off households belong to elites and landlord over the use of forestry resources.

It is also to be pointed out that timber is mostly purchased and used by better-off households since the poor households do not have the need or ability to pay for timber. Since The poorest households do not benefit from the harvesting due to the lack of a legal provision to sell unused products, Community forestry receives wide criticisms for its lack of addressing the poorer households and landless citizens (as cited in Kanel & Kandel, 2004).

Baginski and Blaike (2007) have identified two major interest groups in community forestry sector. One is the powerful members of the CFUG who have hidden interest to control the management of the forest while other is the powerless poor people who have open interest to utilize forest for making their living (as cited in BK 2009, p. 6). Leasehold forestry can be seen as the outcome of the struggle of these two powers centers and solve the problem of inequitable resource distribution by securing the legal rights of poor people to utilize the forest for their living.

Origin of LHF in Nepal

Leasehold forestry came into existence under the Forest Act 1993 and subsequent regulation 1993. Its major objectives were to stop forest degradation and address poorer section of the society by enhancing livelihood options. It came into existence because partly as a supplementary policy for community forestry management where Community Forestry User Groups were being dominated by the elite and higher caste members of the society. Leasehold forestry programs more focuses on equity composition of the forestry user groups.

Kavre and Makawanapur which lies in the central middle hills of the Nepal were the first two districts where LHF program was implemented in 1993. The program spread to 26 districts in 2004. Data suggests that 1,775 LFUGs are already established involving 12,433 households. There is a provision for the land lease of 40 years (Bhattarai 2005, p. 20). Under a LHF programme, a poor household with less than 0.5 hectare land are eligible for holding the leaseland (Sharma, 2006).

The root of LHF can be traced back to the pilot project entitled the Hills Leasehold Forestry and Forage Development Project (HLFFDP) financed under loan by International Fund for Agriculture development (IFAD), but later on government undertook and merged it under the national forest programme. The LHF was designed for the poor specifically aimed at raising the incomes of the families below poverty line through sustainable harvesting of forest based products and to improve the ecological conditions of the hills.

The major agents of leasehold forestry including Department of Forest (DoF), Department of livestock services (DLS), Nepal Agricultural Research Council (NARC) and Agricultural Development Bank were more focused on three major objectives.

a) organize LFUGs and transfer forest resource tenure (mainly degraded land) to resource poor households,

b) provide training on skill development to the members of LFUGs, and

c) Provide small-scale credits to income generation activities, mainly livestock.

International Fund for Agriculture Development (IFAD, 1990) clearly states provision for leasehold household and the land ownership. Only those families are given degraded land for the lease whose income fall below NRs 3,035 per capita income and own less than 0.5 hectre of land. While transferring the use right of a forest, community forestry has got higher priority over leasehold forestry. By law if there is no claim for community forest, then only leasehold forestry provisions are applicable (Bhattarai 2005, p. 20).

Gregorio (2004) has identified rural poor as the one with the weakest property rights and hence facilitating their access and rights to land, water, trees etc were essential to alleviate poverty. Parik (1998) and Angelson and Wunder (2003) reminds that legalizing the property rights and enhancing the collective actions in natural resource conservation as well as combating poverty issues has been widely followed during the past two decades. According to them, the poor are both the victims as well as the potential agents of resource degradation, sustainable environmental protection requires that the poor themselves are made to act as agents of environmental resource regeneration (as cited in Sharma, 2006).

One such paradigm with the poor as the main agent of forest regeneration was the “Leasehold Forestry” (LHF) that was institutionalized in Nepal in the 1990s (Ohler, 2000). The particular policy of leasehold forestry is said to be driven in part by the struggle between donors to get credit for addressing the issue of Himalayan degradation in Nepal.

Understanding Dalit exclusion in Forestry Management

It is interesting to note how Dalits are excluded from the Structure and process dimension of the forestry management sector.

BK (2009) has modeled the exclusion of Dalit in forestry through two different categories i.e. Structure (memberships) and Process (decision implications). Dalit inclusion in the forestry management has been underscored by scholars and the government not only for the poverty alleviation of the poor dalit, who often don’t have land and are deprived of property rights but also to enhance the sustainability of the forestry management committee and concerned institutions. This is expected to serve the twin purposes of addressing poverty and regenerating forests.

Figure 2: Framework of Dalit exclusion in natural resource management sector.

There are both optimistic and pessimistic scenarios of dalit participation in the forestry management institution.

One data shows that representation of Dalits in FUG committees has increased from 2% in 1996 to 7% in 2003. Similarly, another data set from training programs organized in Okhaldhunga district from 1996-2002, however, shows that out of 2,504 participants, only 20 were from Dalit castes. Dalits, who are already suffering from the untouchability issue from the higher caste people, are excluded from the forestry management and access to their vital livelihood options or forestry products.

|

Figure 3 Table showing that Dalits are highly excluded from the community resource management structure |

Scholars have identified several reasons behind exclusion of Dalits in forestry management. BK (2009) claims that Dalits are excluded due to lack of information and investment (p. 4). He justifies the claim by giving the instances of a case study of a CFUG where they have tradition to select dalit women just to fulfill the criteria of both women and dalits representation in CFUGC. The hidden interest of ‘discursive power accumulation understood as an attempt to show that participation of women has increased but this helps them to create post for other. (BK, 2009, p. 5)

As CFUGs are major structure and forest is major source of livelihoods strategy in rural area, exclusion causes to bear huge cost for individual and society in rural areas particularly for the poorest and marginalized society (BK, 2009, p. 5). There is cost bearing to the household, community and sustainability of the institution (p. 6).

The case study shows how decision of committee marginalized forest dependent people who are actual beneficiaries of the timber (BK, 2009, p. 6).

Auction Vs Equitable distribution

A CFUG has huge mass of timber that can be used to improve the livelihoods strategy of the poor CFUG member. The poor CFUG members have aspiration to utilize the timber for making furniture for income generation activities while CFUGC want to increase its fund by selling it outside. (BK, 2009, p. 6) generation activities while CFUGC want to increase its fund by selling it outside. CFUGC favored auction system of timber sale while poor CFUG members favored equitable distribution system with price included in operational plan. Ultimately, in one case of that time, CFUGC decided to sale timber product by auction. They fixed minimum price 4000 NRs. BK, 2009, p. 6) and meeting of 24 CFUGs in the district in 2005. The evidence shows that women and dalits proposed very few agenda in decision‐making forum (BK, 2009, p. 7).

Exclusion from the Process of CFUG

Karna Bahadur Nepali, a member from dalit community cannot sit together with higher caste CFUGC member. He cannot submit proposal and oppose decision taken by the higher caste. If he opposes the decision, he has fear, he cannot get wage work.

Similarly the case study of Thamarjung CFUG of Tilhar VDC of Parbat district shows that the conflict between CFUG committee (often dominated by elites and powerful) and CFUG members (poorer groups) has resulted due to their conflict of interest. CFUG committee want to increase the fund of the committee by selling the timber outside while CFUG members who are poorer than others want to use forestry timber for making furniture and sell them to increase their livelihood option. The auction system of CFUG committee to sell the product has marginalized the access of poorer people who don’t have capacity to buy the product. The benefits are directed towards rich and elite while poorer are being restricted interms of making their living by using forestry product.

.

There are well established literatures suggesting that the Community forestry programme was conservation and protection oriented during its inception in the country. BK (2009) claims that this protection oriented strategy of the programme has marginalized the livelihoods of the more people who dependent upon the livestock management as there were prohibition of the grazing inside the community forest. As a result it has reduced the number of livestock of the rural people as it required stall feeding (p. 8).Similarly, of the total households, largest dalit populations are excluded from good and very good forest. All caste households are excluded from good forest condition (p. 8).

Leasehold forestry (Outside the box)

Figure 4: Picture showing theoretical location of Leasehold Forestry practices in references to different developmental thinking.

It is very important to understand the how the developmental discourse outside the environmental sector influence the policy and practices in the environmental sector. Bhattarai (2005) has elaborated the presence of various discourse and ideologies to locate the concept of leasehold forestry and its particular emergence in the context of Nepal (p. 18).

The emergence of Leasehold forestry in Nepal has been elaborated in narrative manner by Bhattarai. According to him, popularization of Himalayan Degradation theory in 1970s opened the way for western donor to implement massive afforestation project in Nepal through local capacity building strategy. Community Forestry became widely accepted management strategy during 1990s with particular interest on inclusion of marginalized and poorer sections of the society. According to Eckholm (1976), motive behind focusing on exclusion issues was to grasp credit among the competing donors in Nepal who were all working for common objective of forestry regeneration and among the same land area (as cited in Bhattarai 2005, p. 18).

According to Gibson (2000), Agrawal (2001) and Dolsak and Ostrom (2003) Leasehold forestry is influenced by ‘The theory of common property’ which assumes that only the resource user can best preserve and utilize the resources and enhance its sustainability. This theory basically argue if it is proper to hand over power to user groups to shape the rule regarding use of forest or intervene centrally through state mechanism or donor supported actions to manage the resource. Leasehold forestry was initiated under the assumption that only the state enforced policies through donor support can direct the forestry management in proper direction (as cited in Bhattarai 2005, p. 19).

Bhattarai has also linked the four stages of developmental thinking in Nepal and the role of state with the emergence of Leasehold forestry in Nepal. He states that during the period between post-war and 1970s, states were stronger and the main agency of development characterized by authoritarian and oppressive regime. This thinking had resulted in the widening gap between state and the poor citizens who were majority in number. Later during early 1980s, environmental sectors became potential area for western donor to invest and promote development. During mid-1980s, Nepal got caught by Neo-libral policies in forestry sector resulting in market oriented strategy of forestry institution and ignoring livelihood options of poorer section of the society. During 1990s, people started questioning over the methodologies, assumption and kitty-gritty aspects of forestry policies and gave emphasis on local issues and cultural identity. Bhattarai concludes that Leasehold forestry carries the diverse agenda of sustainable development and neo-liberal agenda.

Also, the need of Leasehold forestry can be understood from trend of development practices changing over the time in Nepal. When top-down approaches received wide criticism for not being able to enhance participation of all section of the society, participatory notion of development became widely accepted principle agenda of development. Chambers (1996) put forwarded the concept of ‘communicative rationality’ which emphasizes that citizens must be freed from the manipulative and deliberative process of policy making and simultaneously the public opinion formed through open debate and discussion in non-institutionalized setting of public sphere of citizens should be incorporated while drafting policies (as cited in Bhattarai 2005, p. 19).

Leasehold forestry (Inside the box)

Figure 5: Development of different stages of environmental thinking and its impact on forestry policy of Nepal

Ostrom (2000) and Gregorio (2004) has put forwarded the notion of “Property rights” as the most determining factor for optimal and sustainable management in the discourses of natural resource management (as cited in Sharma, 2006). According to Heltberg (2001) Property right is the claim over future income stream from an asset.

During 1970s and 1980s, property right regime saw a major turning point in its management strategy. Local people were considered the true and the only reliable agents of natural resource conservation at the policy level in the developing countries. According to Dasgupta (1997), the cost and the revenue incurred through the forest provide incentives to the concerned community and hence people were trusted source of protection and promotion of the forest (as cited in Sharma, 2006).

Scholars (Bhattarai et al, 2005) have underlined the theoretical understanding of leasehold forestry in Nepal. According to Bhattarai (2005) the access to forest has close correlation with the poverty alleviation impact because securing right to use forest means securing land right which safeguard the property right of the user. Without these legal rights to forest and land, landless people including poor Dalits are obliged to adopt survival strategies with high level of vulnerability and low resilience towards their daily life threats and basic needs. Hardin (1968) anticipates such scenario to result in frequent degradation of the forestry product and often burgeoning conflict among the resource owners and landless people

The policy of Leasehold forestry and community forestry indicates their common space of conflict while the programs are being implemented in daily life of the users. Since forest has been the major source of income and livelihood for many people living around the forest, conflict occurs regarding the ownership and consumption of the forestry product. Leasehold forestry has defined the criteria for the effective management and use of the forestry product by giving the use right to the general people living within certain boundary of the respective forest. But such provisions are often criticized for its lack of vision[3] to address the local problem of ownership.

Conclusion

It can be inferred that dalit inclusion in forestry management sector is significant not only from the environment protection and sustainable management perspective but also enhancing the livelihood options for poorest sections of the society. This shift in policy changes and thinking is not only the impact of policy at local level interms of different development indicators including poverty index but also their intricate linkages with the changing shift in the development practices and trend over the time.

References

Bhattarai, B., & Dhungana, S. P. (2005). How Can Forests Better Serve the Poor? A Review of Documented Knowledge on Leasehold and Community Forestry in Nepal. Kathmandu: ForestAction Nepal.

Bhattarai, B., Ojha, H., & Yadav, H. (2005). Is Leasehold Forestry Really a Pro-poor Innovation? Evidences From Kavre District Nepal. Journal of Forest and livelihood , 4 (2), 17-30.

BK, N. K., & Gywali, N. R. (2009). Ethno Political Ecology of Social Exclusion: A discourse in Community Forestry of Nepal. Policy recommendation report, DFID Dhankuta and NPC Kathmandu, Kathmandu.

Darnal, S. (2009). Securing Dalit Rights: The case of Affirmative Action in New Nepal. Kathmandu, Nepal.

Kanel, K. R., & Kandel, B. R. (2004). Community Forestry in Nepal: Achievements and Challenges. Journal of Forest and Livelihood , 4 (1), 55-63.

KC, R. (2007, August 31). How can forest be managed sustainably after Sanghiya Sasan in Nepal? p. 2.

Pande, R. S. (2009). Pro-poor community forage production programme in the Nepal Australia Community Resource Management and Livelihoods Project, Nepal.

Sharma, B. P. (2006). Poverty Alleviation through Forest Resource Management: An Analysis of Leasehold Forestry Practice in Nepal. 32. Nepal.

Sharma, B. P. (2011). The Welfare Impacts of Leasehold Forestry in Nepal. Patan Multiple Campus, Tribhuvan University. Kathmandu: SANDEE.

Singh, B., & Chapagain, D. (2005). Community and leasehold forestry for the poor: Nepal case study. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Uprety, B. R. (2000). Social transformation through community forestry: Experiences and lessons from Nepal. Kathmandu: Nepal Swiss Community Forest Project/SDC Nepal.

[1] Literature suggests that approximately 11 percent of the total land area of Nepal, which is often denoted as degraded one, is considered appropriate for conversion into LHF land.

[2] The arrangement is such that to be member of a CFUG, one has to be a resident of that locality. On this ground, Dalit, who don’t have land, are excluded from being a CFUG member. And hence it excludes dalit from multiple benefits including decision making to consumptions and livelihood (Kanel & Kandel, 2004).

[3] Joshi et al. (2000) have reported from the study of the LFUGs through the case study of Kavre that only the rich and elites are being benefitted and eligible for land ownership from Leaeshold forestry program. He has found out in his study that the average distance to the forest of excluded households is 0.35 km and average distance to the forest of the included households is 0.70 km from their settlements. That means the criteria set to include or exclude households from being the user of the leaseholds, not on the basis of who are needy and more local and poor, but on the basis of whose house is located within the area of that particular VDC where forest is located (as cited in Bhattarai 2005, p. 22).

leave a comment